Education Was My Mother and My Father – Georgia Southern’s Sudanese ‘lost Boys’ Bring Hope and Healing to Their Homeland

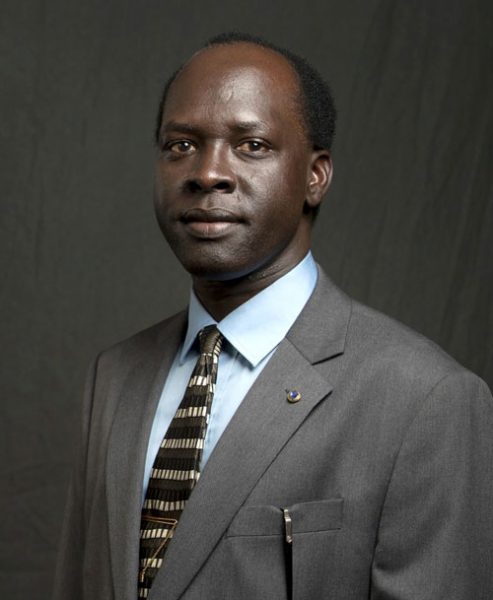

Few people understand the transformative power of education better than Georgia Southern student Abraham Awuol Deng, and alumnus Abraham Deng Ater (’18).

Both enrolled in the Doctor of Public Health program at Georgia Southern in an effort to complete a long, seemingly impossible academic journey that began in the most horrific conditions imaginable — the war-torn region of South Sudan.

“Every time I walked on, thinking I have to forget about what is around me and try to focus on the goal, and my goal was to finish this no matter what happens, no matter the obstacle,” said Ater.

The road that led Ater and Deng to the University was filled with obstacles, and each one held their lives in the balance.

A Journey through Hell

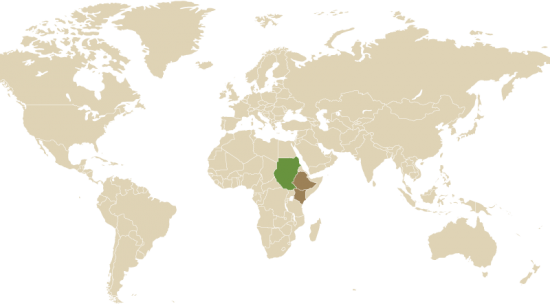

In 1987, before either of them reached 10 years old, Ater and Deng were suddenly separated from their parents and forced to flee South Sudan, which was in the throes of a brutal civil war. With little warning, and little food or clothing, the boys traveled hundreds of miles on foot to Ethiopia, where a refugee camp awaited them.

It was a nightmarish journey. Forced to travel at night, the children were hunted by the Sudanese Army. They were attacked by residents from other villages. Some were attacked by wild animals. For food, they resorted to eating roots, leaves and the remains of dead animals. Barefoot, they made shoes from tree bark, but their feet blistered, cracked and bled.

“It was difficult,” said Deng, who was only 6 years old when he left home. “I was ready to die at the time to be honest. I was just ready to die immediately. That’s what I had in my mind because when I saw my friends and cousins dying in my presence, I just wanted to go with them.”

“I remember my father told me if you think too much about us you will be depressed, you will become very emotional and you will die,” said Ater, who was only eight at the time. “So just focus on what is ahead of you, how to get from one point to another. And that was my focus all that time, just to survive.”

After two months of walking, Ater, Deng and more than 20,000 displaced children reached their destination in Ethiopia. For almost four years, these children enjoyed a pale semblance of normalcy. They were given small food rations, slept in makeshift huts and began to learn English, drawing the foreign letters and words in the dirt.

In 1991, however, the young boys’ “normal” life came to an abrupt halt. A civil war in Ethiopia left the country fractured, and the Sudanese refugees were on the wrong side of political alliances. The Ethiopian Army attacked the refugee camp, pursuing the children as they fled the country.

Deng remembers the pursuit leading them to the treacherous Gilo River, which was raging during the rainy season and infested with crocodiles. As he stood on the bank, frozen with fear, he saw children shot, saw them drown, saw them snatched from the surface by crocodiles, and thought his life had come to an end.

“I didn’t know how to swim, and I could hear the bullets passing by,” he said. One of the older boys grabbed him and convinced him to hold onto his neck and kick his legs in the water as hard as he could. “We jumped into the water and crossed to the other side by God’s grace. I held on tight and I kept kicking my legs and we made it to the other side.”

Deng sprang from the water and ran as fast as he could. He made it a half-mile from the river when a boy who was running beside him was shot down. “I thought I would never make it — that none of us would make it through,” he said.

A United Nations study later found that 2,000 children died that day.

In July 1992, Kenya opened up the Kakuma Refugee Camp to the children, after they made a six-month trek on foot to get there. Out of more than 20,000 children who began the exodus from Sudan five years before, less than half made it to Kenya.

At Kakuma, Deng and Ater found the most stable living situation they’d known in years, however insufficient. They were given clothes, and one meal a day. There were shelters and rudimentary supplies for cooking. Even with this modest stability, however, came more obstacles.

In the camp, which now hosted some 80,000 refugees from Sudan, Rwanda, Somalia and other countries, residents regularly dealt with scorpion and snake bites, bouts of malaria from mosquitoes and other parasitic diseases, and unsanitary conditions that led to deadly diseases like cholera. And with medical care and facilities lacking, many died.

In the midst of the squalor, however, Ater and Deng found hope in education.

In 1987, after the Sudanese Civil War began, more than 20,000 South Sudanese children fled on foot to refugee camps and shelters in nearby countries. They walked more than 1,000 miles to finally reach the Kakuma Refugee Camp in 1992, but less than half of them made it there.

A Promise to Keep

For Ater, especially, education was a priority. When his father sent him away from home, he told him he was sending him away to school, and made him promise to finish his training.

“And that’s the main thing he told me,” said Ater. “He didn’t tell me another thing. He didn’t say to go and get a job and work or anything like that, or you are being sent away for your safety. He was just saying you are going to school. You are going to school and make sure you finish before you come home.”

As early as their days in Ethiopia, Deng, too, had come to see the possibilities of an education, and where it could lead him. Fearing that his parents and his family were dead, learning was all he had left, and represented the only way to reach any kind of future.

“I was obsessed with learning,” he said. “I was always falling in love with learning. So education became like a father and mother to us because we were without parents.”

Even in the worst conditions, the refugees would first make shelters, find food, and then set up a school, asking any adults in their groups to teach them what they knew. In Kenya, the United Nations set up a middle school and high school, providing teachers and some education materials. However, the refugees were responsible for their own pencils, paper and notebooks, which were often difficult to come by.

“So because the U.N. provided food, we would sell some of the food that is given to us to buy those education materials that the U.N. did not provide,” said Ater, who sometimes went three days or more without food to get supplies. “And no matter what happened, I was always thinking about what my father told me, so I would have to force myself to do it.”

Ater and Deng met at Kakuma, studying together with friends and relatives, their work illuminated only by hurricane lamps at night. They both finished high school in 2000, and were eager to continue their academics, but as refugees, their options were few.

“It was very difficult for you to go to a college as a refugee,” said Deng. “We just remained there. Either you could go and teach or you could go and do some other work to support yourself and other refugees. So we thought that was a dead end.”

“And living life there at the refugee camp, there was no tomorrow,” he added. “There’s not, ‘Maybe a better tomorrow,’ because you continue to be faced by the same problems all the time.”

By the late ‘90s, as the war in Sudan intensified, UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency, determined that the children’s hopes for going back to their country or reuniting with their parents were no longer options for them. In 1998, the United States agreed to resettle 3,600 of the lost boys, giving them a chance at a new life.

With only 3,600 places for more than 10,000 lost boys, the three-year selection process was grueling, and education played a large part in whether they would go or stay. They were required to write their stories and later talk about their experiences with U.S. officials. Ater and Deng were interviewed over and over to make sure their stories were consistent while they were vetted for entry into the U.S.

The boys would rush to the sign boards each day to see who had been selected to go. But after a dream, Deng stopped checking the boards.

“I went to my cousin, and I was like, ‘You know what? I don’t think I would go to that board anymore because I had the best dream last night that we were scheduled on June 23. That’s when we are scheduled to go to the United States,” he said.

“And he was like, ‘Abraham, that’s just a dream.’ And I was like, ‘Okay.’ He kept going. And on the 23rd of June you know our name appeared on the board? God brought that to me in a dream!”

On June 26, 2001, Deng arrived in New Port Richey, Florida, and Ater landed in Tucson, Arizona on May 8, 2001. It was their first ride in an airplane, and as they flew over this new country late at night, Ater was spellbound by what he saw.

“When we were on the plane, I looked out the windows and the lights that I had never seen down in all the cities were like — they looked like stars,” he said. “So I was asking, ‘We look like we are above the stars now! And it was so beautiful!”

It was a beautiful beginning to a new life for both of them.

An Opportunity to Change the World

In the U.S., Ater and Deng had a steep learning curve into first-world life. They learned to shop. They learned to cook with electricity. They had to get a GED to get into college, and had to work full time while earning their degrees. Everywhere around them was safety, ease and abundance. It was a difficult transition at first, but led them to realize their purpose.

“I began to think of my friends and cousins that are left at the refugee camp and here I have plenty,” said Deng. “I felt guilty about it. And I struggled with that for a longer period of time. I was like, ‘God, what is special about me? I lost friends. I lost cousins, and I survived all these atrocities, and you brought me to such a wonderful country where there are so many opportunities. So what do you want me to do so that I can impact people’s lives?”

Both Ater and Deng decided to pursue medicine and public health as a way to give back to their fellow refugees. Public health ledt hem both to Georgia Southern for their doctoral degrees, and to be reunited with each other again. They both plan to return to South Sudan to have an impact on those friends and family they left behind.

“At the refugee camp, I saw a lot of things that could have been prevented, health conditions, especially public health conditions that are preventable like sanitation problems,” said Deng. “So public health education would be the key way to prevent or to mitigate these health problems. That’s why I’m very much interested in something related to health.”

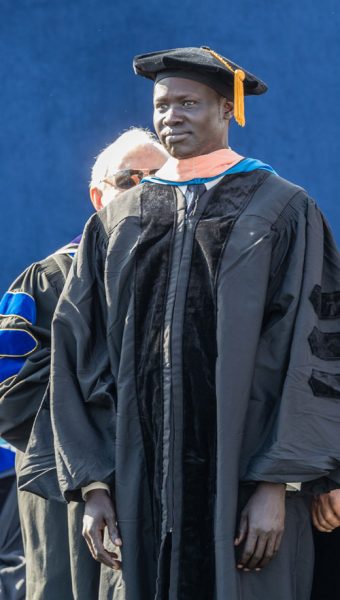

Ater graduated in December of 2018, and dedicated his dissertation to his father. As he crossed the stage at Paulson Stadium, he remembered his father’s words and knew he had completed his goal.

“That’s when I vividly remembered my father’s command, where he was commanding me to not quit, to finish it,” he said. “So it was an exciting moment for me, and to accomplish that, I know I didn’t make him mad. I didn’t let him down.”

Ater created a nonprofit called United Vision for Change which is raising funds to build a school and a clinic in Duk in South Sudan. He wants to keep other Sudanese kids from having to make the journey he made, “so kids don’t have to go to Kenya or Uganda all the way to find an education.”

Both Ater and Deng were reunited with their mothers, some of their siblings and extended family in 2004 and 2006. Seeing them, caring for them and supporting them has only strengthened their resolve to make a difference at home. South Sudan is currently under a peace agreement but it has not ended its war. For now, things are better than they were, and Ater and Deng continue to monitor the situation and look for ways to make a difference.

When they get together on campus or in Atlanta, where several of the former lost boys meet on occasion, they reminisce about their journey, and the impossible grace and providence that led them out of their suffering, and into a world of opportunity.

“Who would have thought that there would be a time for us to even consider going to a college and get a bachelor’s degree, let alone a Ph.D. program, right?” said Deng. “We have to go back to history and think God is wonderful. God does miracles at times, you know?”

– Doy Cave