Eagle Legends and Lore

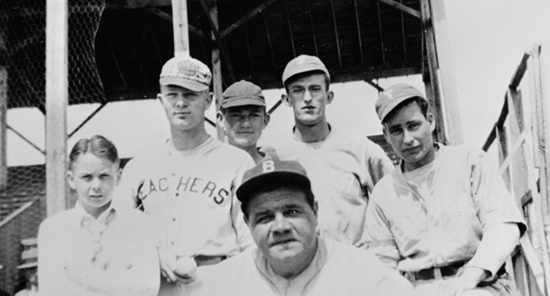

Babe Ruth (bottom center) poses with the staff and students from Georgia Teachers College. Photos courtesy of The Georgia Archives: Vanishing Georgia Collection.

When The Babe Taught the Teachers a Lesson

There’s not a baseball fan in the world who hasn’t heard of “The Great Bambino,” George Herman “Babe” Ruth. But you might be surprised to know he once traveled to Savannah to give the Teachers of South Georgia Teachers College quite a lesson.

A baseball legend, Ruth made his mark in the sport’s history at every level he played, starting with the Baltimore Orioles farm team and moving up to the major leagues with the Boston Red Sox in 1914. He quickly became a superstar. In his first World Series in 1918, Ruth pitched 29 2/3 consecutive scoreless innings, a record that stood for nearly 30 years.

When he was traded to the New York Yankees in 1920, Ruth solidified his reputation as the “Sultan of Swat” with 54 home runs in a single season. When the Yankees built Yankee Stadium in 1923, itwas dubbed “The House that Ruth Built,”and drew more than a million fans that year.

By his last year with the Yankees in 1934, Ruth had seven championship rings — three with the Boston Red Sox and four with the Yankees.

Even after his prime, Ruth remained a beloved figure in baseball. In 1935, when the “Babe” was nearly 40 years old, he signed with the Boston Braves — the National League’s worst team at the time — as manager and player.

On April 11, 1935, Ruth arranged an exhibition game at Grayson Stadium in Savannah and played against a team

of faculty, staff and students from

Georgia Southern, then South Georgia Teachers College.

Grayson Stadium was a renowned park at the time, and the perfect place for an exhibition game. Savannah hosted several baseball greats, including Ty Cobb (who began his career with the Augusta Tourists in 1904), Shoeless Joe Jackson (who played for the Savannah minor league team in 1909) and later Mickey Mantle (who played an exhibition game there in 1959). The stadium was also a temporary home to the 1932 Boston Red Sox training camp.

Fans from Georgia and South Carolina flocked to the stadium to see the “Great Bambino” in action, paying 50 cents for regular seats and $1 for reserved seating.

The Teachers held their own in the first two innings, which went scoreless. In the third inning of the game, however, the “Sultan of Swat” came up to bat and hit a home run over the centerfield fence, scoring four runs for the Braves. By the end of the third inning, the Braves had 11 runs, while the Teachers had none.

Despite the Teachers’ best efforts, the Braves dominated the game, ending with a score of 15-1. Satisfied with his efforts by the sixth inning, the Babe got dressed and left the dugout, meeting a gaggle of eager fans looking for autographs and photos. The majority of the audience left soon after.

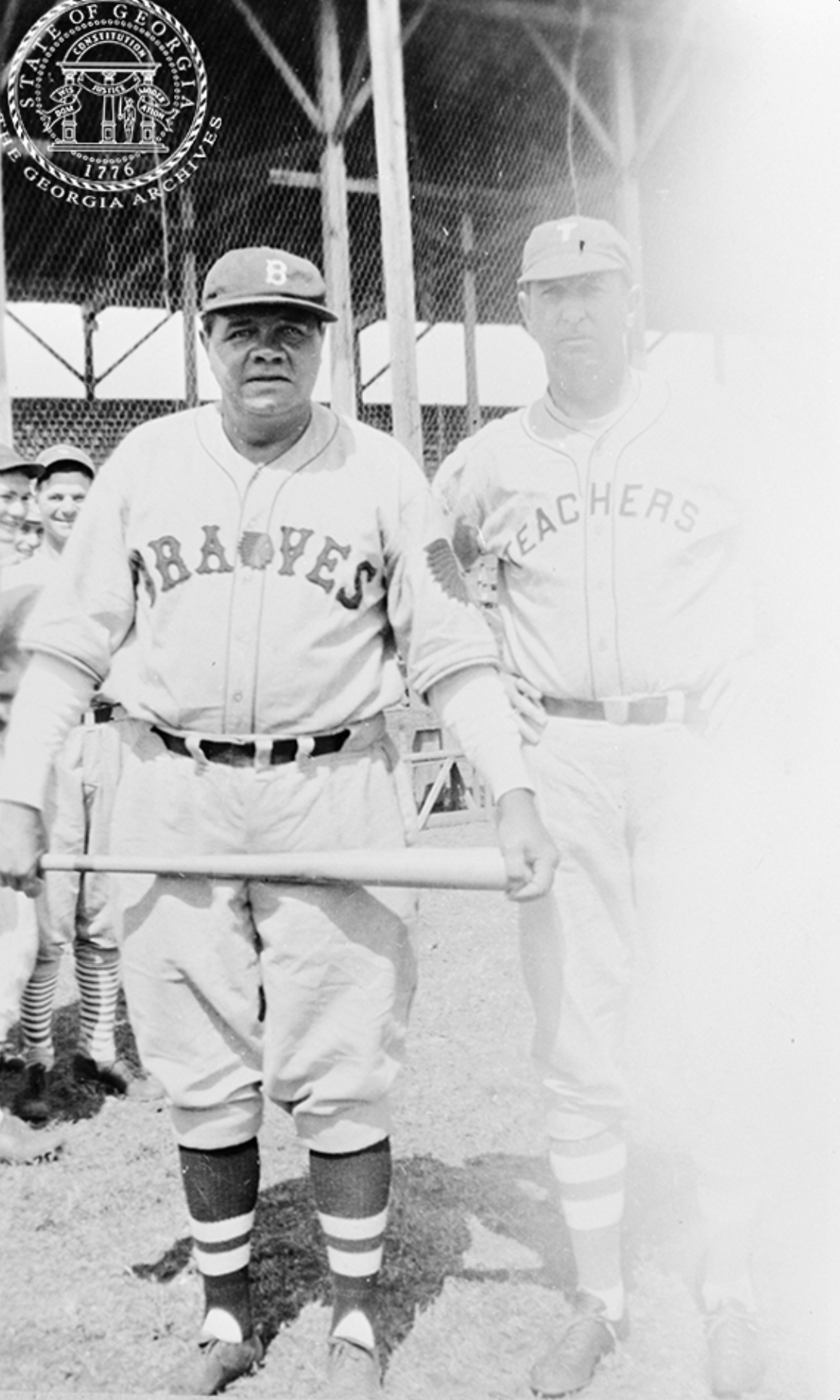

Ruth (L) stands with Teachers player.

Photos courtesy of The Georgia Archives: Vanishing Georgia Collection.

The game was called due to darkness at the top of the seventh inning, but the Teachers had sufficiently learned their lesson by then.

The Boston Braves went on to a horrible season in 1935, finishing the year 35-115 and in financial straits. In 1953, the Braves moved to Milwaukee, and then in 1966, they moved to their current home today — Atlanta.

— Doy Cave

An Admirable, Independent Woman

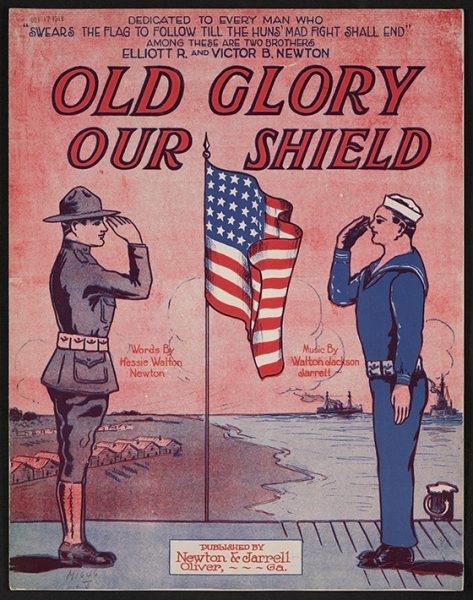

Hester Walton Newton, namesake of the Newton Building on the Statesboro Campus, was a history and science professor for years at Georgia Southern. But did you know that she was also a professional lyricist?

Born in 1883, Newton, a historian who lived through two World Wars, joined the faculty in 1928 when Georgia Southern University was Georgia Normal School. Before becoming a professor, Newton gave writing popular music lyrics a try. Known at the time as Hessie, she wrote the words to fellow Oliver, Georgia, native Walton Jarrell’s music for the patriotic tune “Old Glory Our Shield,” as a recruiting tool and rallying cry for soldiers that left for battle at the beginning of World War I.

This was the golden age of sheet music. Initially, sheet music was the primary means of circulating songs. Before records were widely distributed, sheet music was the way that popular songs got into people’s hands. Many households were filled with music as family members and guests gathered round the increasingly fashionable piano to sing popular sheet music titles. In the early 1900s, the pianos used in American homes increased more than five times as fast as the population.

Newton and Jarrell’s composition was dedicated to two brothers, Elliot R. and Victor B. Newton, both service members headed into battle. The piece was “Dedicated to every man who swears the flag to follow till the Huns’ mad fight shall end,” which was written on the title page of the sheet music.

Newton was also infamous as one of the professors who was purged from the college for her loyalty to President Marvin Pittman, who was fired by Georgia’s segregationist governor Eugene Talmadge for championing integration. The impact of Talmadge’s actions made front page news nationally and resulted in the loss of accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools for all white colleges in Georgia.

The loss of accreditation resulted in statewide protests against Talmadge.

Pittman reclaimed his position 18 months later when Talmadge lost reelection and Newton rejoined him at what was then known as Georgia Teachers College.

Besides teaching a variety of courses throughout her tenure, Newton was dorm director in Anderson Hall, Lewis Hall and the Health Cottage. The suggestion to name the academic building for the history professor came from former social science division chair Dr. Jack Averitt, who described her as an “admirable, independent woman.”

Newton retired after the 1952-53 school year and died in 1968. Her framed photograph resides in the Newton Building, and one of the original copies of “Old Glory Our Shield” resides in the Library of Congress. — Liz Walker