A gut feeling: Georgia Southern researchers exploring how the gut microbiome adapts and shifts in endurance athletes

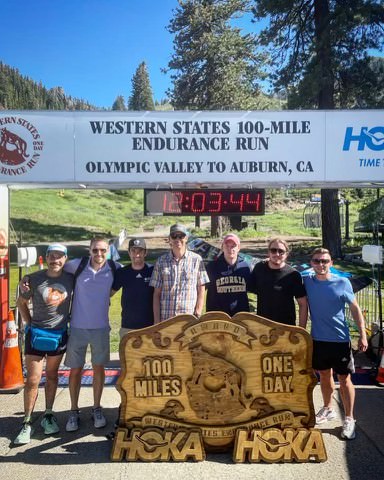

The summer before James Brown began his graduate school career at Georgia Southern University, he found himself alongside Waters College of Health Professions Associate Professor Greg Grosicki, Ph.D., in Tahoe City, California, surrounded by more than 40 of the world’s most elite athletes and about half a dozen researchers.

Brown, who chose to pursue his master’s degree at the Armstrong Campus in Savannah, was getting a head start on his graduate assistantship. Under the advice of Grosicki, Brown helped collect data for a large-scale research study to see how the gut microbiome changes in athletes during the Western States Ultramarathon, the world’s oldest 100-mile footrace.

While Brown was still at Coastal Carolina University, Grosicki reached out to see if he’d like to participate in research during one of the world’s foremost endurance tests. Heading into new territory, Brown agreed.

“I didn’t know much about the gut microbiome,” he said. “I had never done anything in terms of research with it, so it was a huge learning experience for me.”

The gut microbiome refers to a collection of bacteria, viruses and microbes that reside in the gastrointestinal tract. It has even been described by some as a second brain.

“There are 39 trillion bacterial cells in the gut,” Grosicki said. “To put that in perspective, our bodies are made up of 30 trillion cells, so there are actually more cells living inside of us than we are composed of, which I think is pretty cool. It makes you think, are we actually living on these bacterial cells or are they living in us? It’s pretty crazy to wrap your mind around.”

Grosicki, who began researching how gut microbiome changes as humans age during his postdoctoral work, saw there was limited research on how exercise might change the gut microbiome.

“What I’ve learned over the course of my career is that exercise is really the magic bullet,” Grosicki said. “There’s no exercise pill. It can’t be put in a pill. No one’s going to be able to ever develop it because there’s just absolutely no way to capture the therapeutic benefits of exercise in a single supplement. I wanted to know what happens to the gut microbiome when we exercise, and that’s really been one of my primary missions as a scientist at Georgia Southern.”

Grosicki partnered with fellow researchers Jacob Allen, Ph.D., from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Jimmy Bagley, Ph.D., from San Francisco State University, and Jamie Pugh, Ph.D., from Liverpool John Moores University, who helped conduct the study. The research team recruited 43 athletes to participate in order to examine how gut bacteria shifts during intense and extremely long bouts of exercise as a means to better understand the organ overall.

“The Western States Endurance Run represents what we like to say is like the epitome of extreme human physiology and possibly the world’s best human performance lab because we’re able to study the human being and the human condition in the most extreme circumstances,” Grosicki said. “Besides killing someone, you really can’t get any more extreme than what these people are going through. They’re running 100 miles at 8,000 feet elevation in 110 degree heat. To really understand how the human body works when we study it in extreme conditions like this, we’re really able to glean insights that there’s absolutely no way we could recapitulate in a laboratory environment.”

Brown is looking forward to what the results from the lab tests and data collections will tell the research team.

“There’s a lot of information on exercise and there’s a lot of information on the gut microbiome, but there’s not a lot looking at the interactions between the two and especially in ultramarathon runners,” Brown said. “We think we have data that could show huge extremes which is a big talking point in this type of research. Hopefully we will see some cool data and we’re able to pick up some good stuff.”

Grosicki echoed this sentiment, noting the variety in data will show even more.

“We were lucky to get the 43 athletes,” he said. “One of the things that was so cool about this time is we had about three or four of our athletes in the male and the female top ten. So we have some of the fastest in the race, and for that matter, some of the best athletes in the world.”

Data from these athletes will help Grosicki and his colleagues build upon results from 2019 when he studied a single ultramarathon runner and observed a significant shift in human gut bacteria.

“At the time, we reported what was and still is the most rapid and profound shifts in human gut bacteria following a single bout of exercise ever to be reported in scientific literature,” Grosicki said. “The most striking change we saw was a specific bacteria that metabolizes lactate, which is produced during exercise. The body takes that lactate and turns it into fuel that can then be put back into circulation and used by the body for exercise.”

Many variables affect the shifts in gut microbiome, Grosicki noted, which is why their ultramarathon team collected pre- and post-race blood and stool samples, learned about each athlete’s medical history and training, looked at race-day factors, diet and more. Additionally, having both biological male and female and varying age data from the race was important.

“Our athlete in 2019 was male and we know that biological sex can play a huge role in these physiological adaptations and the gut microbiome,” he said. “We were very intentional in trying to recruit a sample of both males and females. We’re also going to be able to look at biological sex and age. We had people in their 20s, we had some people in their 60s. We can control for these biological variables such as age and sex, and see how those may influence the gut bacteria and their response to exercise as well.”

Grosicki in October 2022 furthered this line of research at the Ironman World Championships in Kona, Hawaii, where he and colleagues gave half of the athlete participants a probiotic supplement for four weeks prior to the race.

“When finalized, these data will help us to better understand, one, whether a probiotic supplement truly alters the gut microbiome of athletes, and two, whether a probiotic affects how the gut microbiome responds to exercise, and three, whether a probiotic may alleviate gastrointestinal distress and improve performance in athletes,” Grosicki said.

While the full results from these studies won’t be complete for some time, Grosicki is optimistic about the data and that it will lead to a greater understanding overall of gut health, which in turn will lead to greater understanding of overall human health.

“The gut microbiome is constantly evolving,” he said. “When we look in the literature, there are a lot of large-scale epidemiological studies showing links between age-related changes in those gut bacteria and a number of clinical conditions from things like cardiovascular disease to cancer. There’s even data now linking COVID-19 and some of the associated symptoms and side effects to changes in gut bacteria. So, we know that this gut microbiome is a very powerful influencer of human health.”

Grosicki and Brown intend to return to the 2023 Western States Endurance Run in June to conduct another study, but this time they will focus more on the cardiovascular system (heart and blood vessels) of the athletes.

“More specifically, we are hoping to learn how participating in ultra-endurance exercise affects blood vessel function, and the impact of these blood vessel alterations on the heart and kidneys,” Grosicki said.

Addition, the two were recently awarded a grant to study the relationship between salt and fiber in the diet and vascular health.

“This grant will help tie in the interests that we have both in the gut microbiome and the cardiovascular system,” Brown added.

Grosicki is excited for Brown to experience this type of research setting early in his graduate career, describing it as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

“It was cool to see James contribute right out of the gate,” Grosicki said. “I was able to give him tasks specifically. He communicated with all the participants, which is no joke when you’re a master’s student, all of a sudden being thrown into networking with 43 athletes over the course of two days. He pulled it off with flying colors. He definitely exhibited over the course of the week a very strong work ethic. He never complained about having to get anything done. Those will be traits that will definitely serve him well during his studies here and going forward.”

For Brown, the most interesting part was the interactions with the athletes themselves.

“To be able to run 100 miles nonstop — I can’t imagine the kind of dedication that it takes,” Brown said. “On the other hand, it’s just crazy that the human body can withstand that. It truly puts into perspective what people are capable of if they really put their minds to it.”

The experience helped Brown improve his communication skills, which he believes will benefit him throughout his academic and professional career.

“That was the coolest part, just seeing that they’re just normal people like everybody else,” he said. “It was really fun to talk to them.”

Grosicki believes Brown’s participation in this research is vital to his success as a student.

“The more experiences that our students can have, the more successful they’re going to become,” Grosicki said. “The primary reason that I hired James as a graduate research assistant is because he’s very motivated to go on and get a Ph.D. I think what is catalytic to his success is being exposed to these types of things, and gaining exposure and networking. I am undoubtedly a product of my environment, and I would not be where I am without my collaborators.”

Brown, who is interested in cardiopulmonary research, appreciated that Grosicki was supportive of his thesis goals and worked to find a way to incorporate Brown’s interests into his assistantship.

“Dr. Grosicki and I have great conversations,” said Brown. “He knew what I was interested in, and he said that he would help cater around that,” Brown said.

Posted in Press Releases